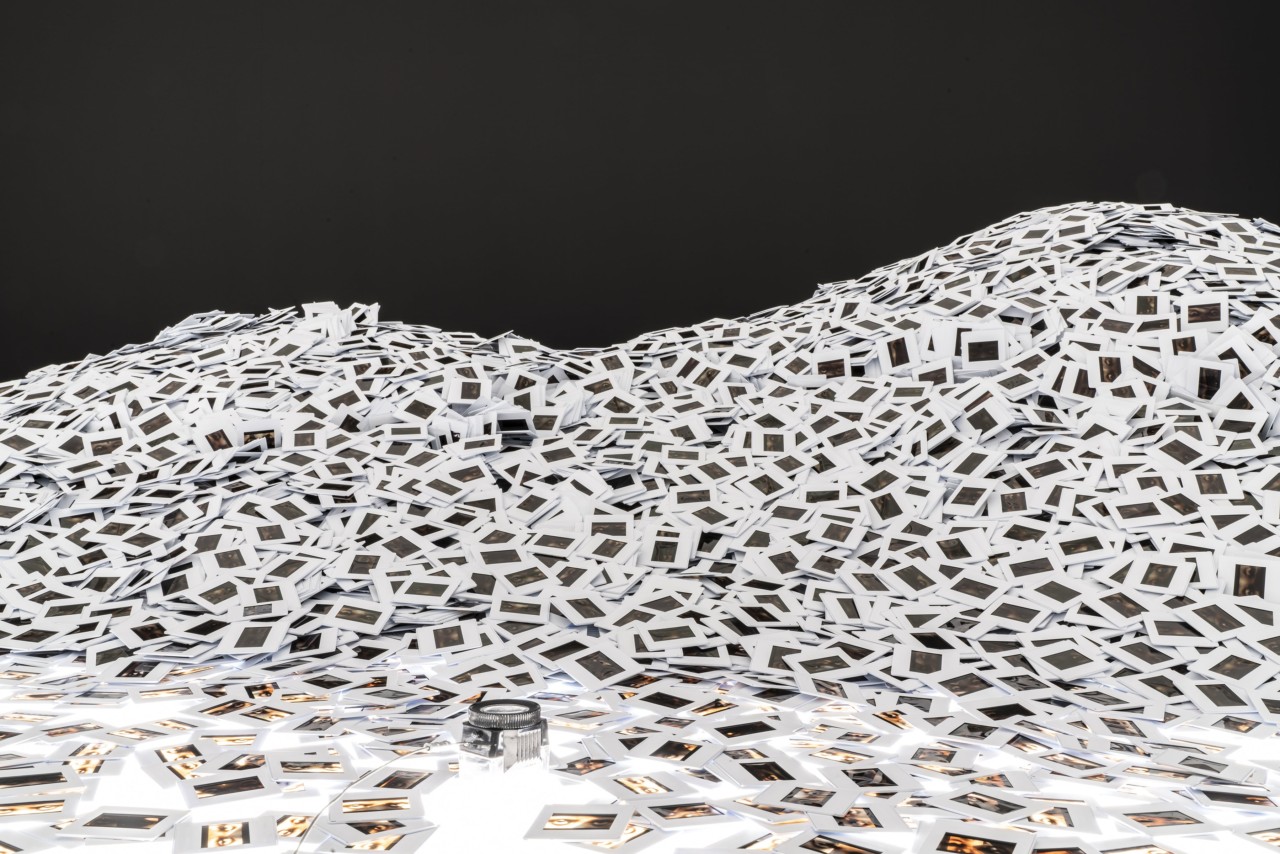

Installation view of 'Alfredo Jaar: 25 Years Later' at Goodman Gallery, London.

The aim of the Chilean-born conceptual artist, filmmaker and architect Alfredo Jaar is ‘to make art out of information most of us would rather ignore’. His most renowned body of work, the six year long The Rwanda Project, which deals with the Rwandan Genocide of nearly one million people in 1994, is centred on his ongoing questioning of photography’s capacity to evoke emotional reactions and social responsibility.

Now, 25 years after the genocide, a selection of Alfredo Jaar’s powerful commemorations goes on show for the first time in the UK at Goodman Gallery, a gallery from Cape Town that opened its London branch this October.

Enraged by what Jaar described as the ‘barbaric indifference’ of the Western world to the killings, mostly of the Tutsi tribe in Rwanda, he decided to travel to the country to document the aftermath of the humanitarian catastrophe in August 1994. ‘I think it’s my duty and my privilege and my responsibility as an artist to try to bring some light to these realities that are being ignored by the media’, is how he described his motivation.

Jaar spent three weeks in Rwanda, meeting people in refugee camps and listening to their personal stories, as well as taking photographs and filming them. He also visited the neighbouring countries Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo), Burundi and Uganda where millions of Rwandan civilians had fled.

The centrepiece of the exhibition, The Silence of Nduwayezu (1997), consists of an overwhelming mound of slides piled up on a huge light table, bearing resemblance to a mass grave. Each of the million slides here features a close-up view of the eyes of a five-year old Tutsi boy called Nduwayezu, whom Jaar met at a refugee camp in Rubavu. We can read on the wall before we enter the installation that Nduwayezu, like countless other children, had witnessed the violent murder of his parents, leaving him so traumatised he had not spoken for four weeks.

The aim of this piece as Jaar states is to humanise the genocide, to bring Nduwayezu’s personal story to the viewer’s attention. ‘When you have a tragedy of a million deaths, it’s meaningless, it’s too abstract. So it’s important to reduce the enormity of the tragedy to one story, to one name. This way people can identify with that person and feel solidarity or empathy’.

The viewer is invited to take a close look at the eyes of the boy with magnifying glasses and, without depicting actual scenes of violence, the image of the boy’s eyes. Jaar decribed them as the saddest eyes he had ever seen, telling the infinite stories of suffering, pain and loss during the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

Children also feature in other photographic work in the exhibition. Six Seconds (2000) shows an out-of-focus shot of a girl who is turning her back to the camera. The artist met the girl in 1994 in the Nyagazambu refugee camp but after just six seconds, when she learned that her parents were murdered, she turned around and left. For six years, Jaar held onto the picture, convinced he could not use it, but later realised that the fuzzy quality perfectly expressed photography’s ‘incapacity to represent a certain reality—everything is always out of focus’.

The negligence of the unfolding human tragedy by the domestic US media is also revealed in the installation Untitled (Newsweek) (1994), a selection of 17 covers of the US magazine that are installed on the wall of the gallery’s basement. Dedicated to sports, celebrities, and financial issues, they were published during the three-month period of the Rwandan genocide. It was only 17 weeks after the massacres in Rwanda had started, and the monstrous death toll had reached one million people, that the magazine dedicated its first cover to Rwanda. Underneath each cover we can read captions written by the artist documenting the development of the genocide taking place concurrently in Rwanda.

25 Years Later makes us aware of how our Western perception of the African continent is still a story of absence, racism and marginalisation, shaped by the media and international politics. Sitting between ethics, politics and art, it is a powerful exhibition that makes a compelling commentary on the power of images to translate human tragedy. Alfredo Jaar’s commemoration of the genocide offers us a critical view of the dramatic events in Rwanda that many of us might have forgotten or were not even aware of.

Rather than competing with the overwhelming and seemingly interchangeable flow of mass media images of global violence, a flow that makes us indifferent instead of empathetic, Jaar employs visual strategies such as the infinite repetition of a cropped image or a close-up of a personal scene. This slows down the viewer’s process of looking in order to evoke deeper emotions in the spectator.

Questions of representation, particularly of Black bodies, have become increasingly relevant in recent years and Jaar’s The Rwanda Project plays an important part in bringing some light to realities that are being ignored by the media. I saw Jaar’s The Rwanda Project for the first time as a student in an exhibition in Ottawa, Canada, shortly after its completion in 2000. 20 years on, it still has the same horrifying and powerful effect. 25 Years Later is a timely reminder to constantly reflect on how the media play a key part in the presentation of history and politics, but also how the form of their narratives interprets the world around us.

Christine Takengny

Curator

Goodman Gallery, 26 Cork Street, London W1S 3ND. Open Tuesday-Friday 10.00-18.00, Saturday 11.00-16.00. Exhibition continues until 11 January 2020. www.goodman-gallery.com