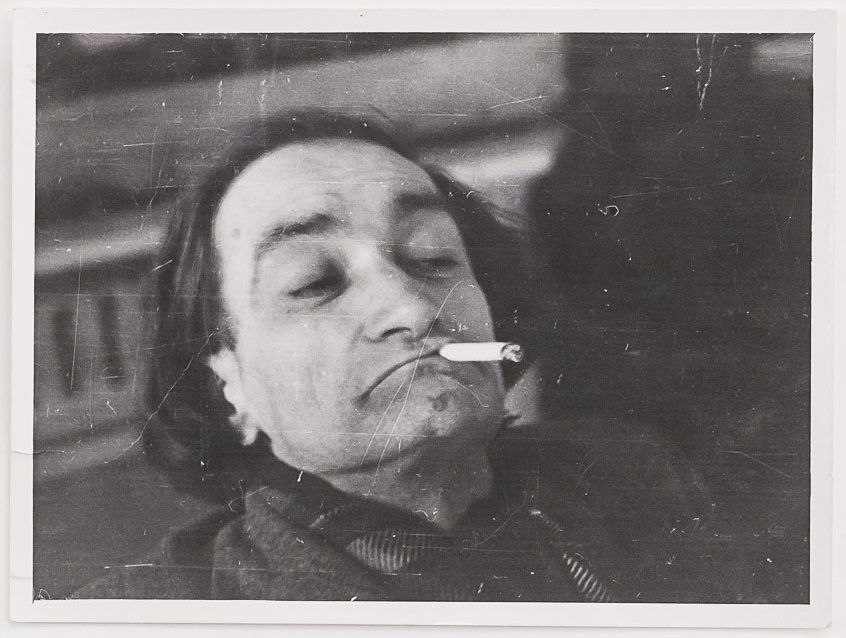

Georges Pastier, Portrait of Artaud, 1948. Vintage print, 11.6 x 8.6 cm. Courtesy the Bibliotheque national de France and Cabinet, London

Antonin Artaud was transferred to the psychiatric hospital in Rodez, Aveyron, in February 1943. He had been confined to psychiatric hospitals in or around Paris since 1938, but the outbreak of war in 1939 lead to such shortages of food and medicine that conditions there declined alarmingly rapidly, as did Artaud’s health. Artaud was released from Rodez in 1946, and lived the remaining two years of his life at a private clinic in Ivry-sur-Seine.

Born in Marseille in 1896, Artaud began writing poetry in his teens and by the 1920s had established himself as an often controversial figure in the Parisian avant-garde. A friend of prominent writers such as André Gide and Alfred Jarry, he was also associated with the Surrealist movement until he was expelled from the group in 1926. Artaud wrote his radical and enduringly influential Manifesto for a Theatre of Cruelty in 1932 having already spent a number of years intensively involved in experimental cinema. Luis Buñuel’s masterpiece of Surrealist film, Un Chien Andalou, 1929 is said to owe a debt to Artaud’s hallucinogenic film screenplay The Seashell and the Clergyman, 1927.

The exhibition now at Cabinet Gallery features a selection from 406 notebooks that Artaud produced in the last years of his life. Always perilously impoverished, these were the cheapest available medium for his outpourings of writing and drawing. Together with the majority of his drawings, the notebooks were entrusted by Artaud to his close friend Paule Thévenin, and on her death bequeathed to the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 1993. The extensive series of large format – and relatively formal – portraits of friends and acquaintances that Artaud made in his final years in Ivry were the subject of an exhibition at MoMA New York in 1997. However these notebooks, that reveal so searingly the tumultuous thoughts of the artist through the same period, are far less known.

The compulsive urgency of Artaud’s production in these notebooks is unmistakable. Both text and drawings are executed in pencil that drives into the paper. Sometimes legible, sometimes what appear to be a visceral translation of pure rage, the drawings sit alongside diaristic fragments, spells and extraordinary lists.

“(…) no drawing done on paper is a drawing, the reintegration of a strayed sensibility,

it is a machine which has breath

it was first a machine which at the same time has breath

It is a search for a lost world

And one that no human tongue integrates.”

Cahier 285, trans. Clayton Eshleman

Bodies are drawn spotted with markings made so heavily they threaten to pierce the squared paper of the notebooks; daggers in many forms recur as a motif, recalling Artaud’s travels in Mexico and his fascination with the rituals of the Tarahumara Indians, with whom he lived with there. The artist’s handwriting veers between neat copperplate and a loose scrawl, mirroring the effects of using the laudanum and other opiates that he had been addicted to since his late teens. Image and text exist side by side and indistinguishably on densely worked pages.

Artaud’s depictions of the human body – machinistic, dismembered, surrounded by flying nails – translate the agonies of his life physically as well as psychically. Between June 1943 and December 1944 Artaud was subjected numerous times to the new electroshock therapy, enthusiastically, if inexpertly applied by Dr Gaston Ferdière at Rodez. Convulsions during the first of these sessions (administered without anesthetic) resulted in broken vertebrae. A photograph of Artaud taken by Georges Pastier at this time shows a man ravaged. After leaving Rodez he described the experience of the electroshock to a journalist: “I plunged into death. I know what death is.”

Artaud raged in his notebooks against these attempts to control, cure or socialise him. The only sphere of freedom, the only means of expression available to him was on the pages of the notebooks, and here he takes aim at his tormentors, as well as continuing his struggle with the Catholic faith in which he was brought up.

“The body is a multitude driven wild, a kind of travelling-trunk with many compartments which can never have finished revealing what it conceals." Histoire Vecu d’Artaud - Momo, trans. Stephen Barber

The body is at once the site of all suffering and the source of all thought and creation; the notebooks are full of notations akin to the physical hurling of this body against the paper. They bear the literal texture of Artaud’s life: the stains, creases and cigarette burns from being carried about in the artist’s pocket.

The exhibition at Cabinet Gallery is based on several years’ research, and brings to London a body of work never before seen here. It is an important opportunity to examine an aspect of Artaud’s production that few have had access to, and to reacquaint ourselves with the extraordinary intellect that has influenced generations of artists and writers since.

Caroline Douglas

Director

Cabinet, 132 Tyers Street, Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, London SE11 5HS. Open Thursday-Saturday 12.00-18.00. Exhibition continues until 6 April 2019. www.cabinet.uk.com