Image courtesy the artist and Holly Bush Gardens, London. Photo Andy Keate

Courtauld Gallery, Somerset House, Strand, London, WC2R 0RN

29 September 2023 – 14 January 2024

One day in the summer of 2020 I cycled to Hollybush Gardens gallery to view a drawing by Claudette Johnson that had just arrived. Masked up and appropriately distanced from the one member of staff there, I watched as the drawing was unrolled in front of me. What emerged was Doing Lines 1 (Lockdown) Line Journeys, 2020. I cannot satisfactorily express the effect of that encounter on me: the careful reveal of the self portrait, the artist contemplating herself with dispassionate gaze, seemed to encapsulate the stasis and isolation of the moment and the way we were all forced to draw on our inner resources. There is something in the combination of the set of the jaw, the hand-on-hip rootedness, and the questing, delicate line that draws and redraws the figure that makes it an absolutely magnetic work. Happily, that drawing is now in the collection of the Herbert Art Gallery in Coventry, courtesy of our Rapid Response Fund that year.

In her current solo exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery, the second, larger room examines Johnson’s oeuvre from the last eight years, years in which her reputation has soared through Thin Black Line(s) at Tate in 2011, The Place is Here at Nottingham Contemporary in 2017, and her solo exhibition at Modern Art Oxford in 2019, to name but a few highlights of a rapidly expanding CV. Here there are two more self portraits, fully worked in pastel and gouache: Standing Figure with African Masks, 2018 and Figure with Figurine, 2019. In each, our eyes meet the downward gaze of the artist, in the first work her hand on her hip, in the second her arm cranked up, over her head. Her figure, a powerful diagonal form, fills the picture. Her pose in either work makes reference to Picasso’s threatening, sexualised Demoiselles d’Avignon, a painting that appropriated images of African art to revolutionise Western art at the beginning of the 20th century. But where the Demoiselles are posed with raised arms in order to offer their nude bodies to best visual advantage, Johnson’s stance serves to take up the most space in the picture plane. These steadily appraising portraits are of a woman with experience of life etched in her face. The artist appears to be at the height of her powers.

Claudette Johnson works from life, from models, from photographs and from her own imagination. Usually the same large format, her portraits present their subjects at perhaps twice life size. The monumental Reclining Figure, 2017, at 257cm wide is so large as to almost feel like a landscape, an effect reinforced by the strip of brilliant blue background at the top of the image. The wall label describes the inspiration behind the work as a photograph that reminded the artist of the way her own mother would lie down on her sofa to rest at the end of a long day’s work. The head, and the arms on which it rests, are carefully worked – the subject’s eyes are fixed on something beyond the frame of the image in a moment of introspection. Her body, in a loose dress, is suggested by a series of tender lines that translate the softness of drapery and the body at ease beneath it. Look again and it could be a sketch of a mountain landscape with ridges and escarpments.

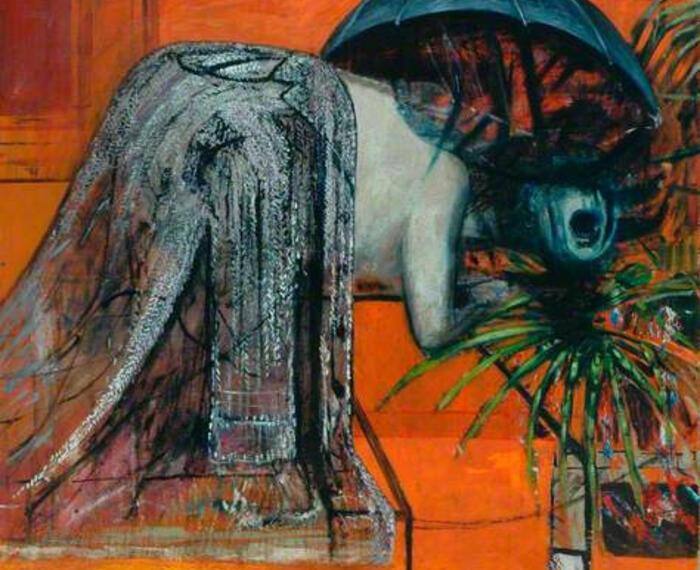

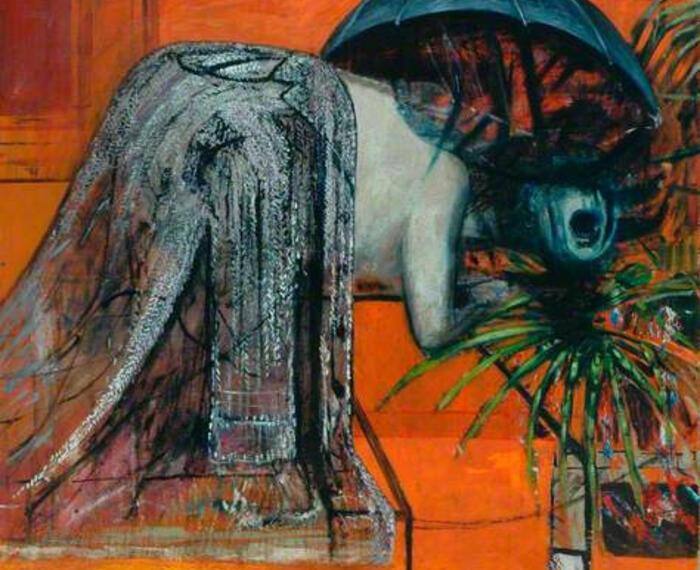

Since the very beginning of her career, Johnson has been concerned to counter the invisibility of the Black subject, with work that places them front and centre as individuals with agency. Scale is critical here. It is political in relation to a Western art history in which the Black figure has almost always been depicted as smaller, or literally marginalised at the edge of paintings. The Black servant is a trope of aristocratic portraits of the 17th and 18th centuries. The first room of the exhibition holds six paintings dating back to the early 1980s. Having been born in Manchester in 1959, Johnson attended Wolverhampton Polytechnic and the BA Fine Art course between 1979 and 1982. The two earliest works here, both from 1982, show the artist grappling with the legacy of Picasso’s modernism, deploying abstract forms as the background to nude figures that are themselves partially abstracted or fragmented. Already the figures, dynamic and assertive, fll the whole space of the picture; and right from the start we find the zig-zagging line bisecting the image – a device that recurs up to and including the most recent painting here, Blues Dance, 2023.

In And I have my own business in this skin, 1982, the line runs between the figure’s legs and up and between her breasts, disappearing off the top of the paper. In I came to dance, also 1982, the figure, which somehow recalls photographs of Josephine Baker dancing, is in front of the zig-zagging line, as is the central figure in Trilogy (Part Two) Woman in Black. The angles of the bisecting line echo the angles of the model’s raised elbows, pressing out to each edge of the image. The artist makes no preparatory sketches, or only very minimally, the work taking shape, being worked out, in the moment on the paper. She has described this bisecting line as part of the process of working out the composition. The Woman in Blue and Woman in Red who make up the flanking parts of the trilogy engage the viewer with unwavering eyes, asserting their selfhood as Black women, in defiance of prevailing stereotypes. And some of those stereotypes of Black womanhood are readily available here at the Courtauld, in Gauguin’s depictions of young Tahitian girls, for example.

If we have been late to catch up with the importance of Claudette Johnson’s central place in British art history, then this exhibition, and the fine, scholarly catalogue that accompanies it, are putting that to rights. The essays by the Courtauld Institute’s Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art and Critical Race Art History, Dorothy Price, go into welcome detail about the artist’s contribution to the often-cited First National Black Art Convention in 1982, as well as offering an in depth discussion of the artist’s influences, networks, and techniques. I would like to suggest this is a ‘moment’ not only for the artist, but for the institution that is the venerable Courtauld Institute. But go to see the show for the sheer emotional intensity of the work, the beauty and the tenderness.

Caroline Douglas

Director

The Courtauld Gallery

Somerset House, Strand, London, WC2R 0RN

Opening Times: Monday - Sunday from 10am to 6pm

Exhibition open until 14 January 2024