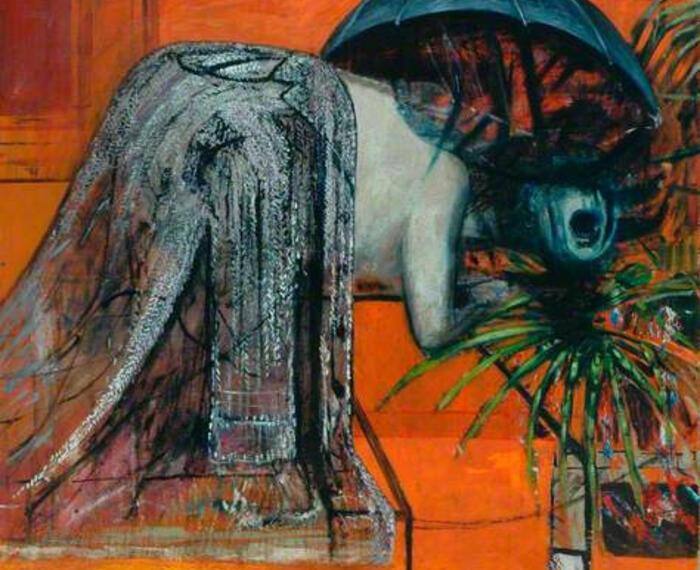

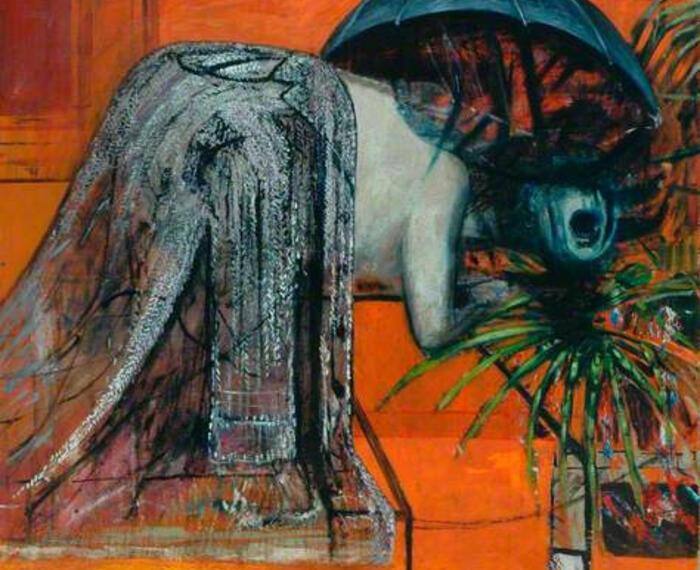

4 Dozen Minus 1, Courtesy the Artist, Corvi-Mora, London

Having one foot planted in utility, in the ordinary, can nourish the aesthetic. Work can come and go between these poles. Use and Beauty for Leach were supposed to be poised in equal parts; but clearly the balance can be shifted, and the meanings of both words seem now, after the developments of the last 20 years, a great deal more elastic and open to argument.

Alison Britton, Use, Beauty, Ugliness and Irony, 1993 in Alison Britton: Seeing Things, 2013

An egg box is a paragon of industrial design: made of many-times recycled paper, it holds its half-dozen charges lightly, carefully and stackably. In terms of aesthetic as well as use value the box is only superseded in its economy by the egg itself: nature’s most perfectly adapted container for moving matter from one place to another.

Eggs are a recurring element in Dan Coopey’s work – strung together or cocooned singly in woven structures that reference the tools devised in pre-industrial societies. In 4 Dozen Minus 1, 2025, 47 celadon blue eggs are packed in to a shallow basket, trapped behind an irregular mesh of waxed thread. The hand-woven rush form acts as a frame and mounted on the wall here the sculpture takes on a pictorial quality. These eggs could be on their way for sale from a rural smallholding, carried in a vessel made by the farmer, themselves from locally available material. It’s an odd number, four dozen minus one: we still sell eggs by the dozen, apparently, as a hangover from Imperial systems of measurement (twelve pennies in a shilling etc.). In the medieval period baskets – bushels - were themselves a unit of measurement, used for the payment of tythes to landlords although, as the exhibition notes point out, they were not a wholly reliable measure.

Potgaston, 2025, Courtesy the Artist, Corvi-Mora, London

Many of Coopey’s sculptures contain something, though this is often only to be understood from reading the list of materials. Jacob, 2024 sits on the floor and has a form akin to a buoy. Loosely braided ropework encloses dark brown sheep’s wool, and suddenly we are aware of how divorced we are, as city dwellers, from the trade in raw commodities – something that disappeared from the wharves of port cities here almost a century ago. Parcel and Potgaston look like merchandise that could have pitched up in the Pool of London from another continent. The latter title, however, is the name of Coopey's grandparent's farm in rural Gloucestershire where Coopey grew up, the grandson of sheep farmers, themselves adept in traditional crafts.

It is an area of England renowned for basket making, though that has been in decline since the 1980s. Basket making is a determinedly rural craft, its most well-known British proponent being David Drew, who famously plants, harvests and weaves his own willow. Drew left his native Somerset for France; Coopey now lives and works in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Many of the fibres he uses are bought locally, the eggs come from the market near his house. He is acutely conscious of the traditions of basketmaking and weaving, simple plaiting and knotting techniques, found in societies across the world. These are examples of an ancient technology (said to predate vessels made in clay) closely associated with commerce and trade. Potgaston’s materials are listed as ‘water hyacinth, sisal and wooden crate’. The crate appears to be loosely wrapped in woven fibre, then neatly strapped in a grid of orange sisal twine; it is unmistakably cargo. Iris, 2025 has a homely, improvised look – as if prepared only for a short journey. Dried flowers are held inside a finely woven rattan vessel, loosely lashed with twine into a triangle shape.

Beer Belly, 2024, Courtesy the Artist, Corvi-Mora, London

Beer Belly, 2024 is an altogether different proposition. At almost human height, its shaggy, slumped form is half collapsed on a found wooden stool. It has anthropomorphic rolls and love-handles like a bar room regular and is easily the most charismatic piece here. Nominally a vessel, there is an aperture where the form narrows at the ‘head’, this sculpture expresses most vividly the bodily engagement of the artist with his material. Physical strength is required to keep the twine under tension in order to weave it; this piece must have demanded a whole-body engagement to create something at such a scale.

Auricle, 2025, Courtesy the Artist, Corvi-Mora, London

Auricle, 2025 is another non-functional object, but one which references functioning parts of the human anatomy: the auricles of the ear or heart. Soft and irregular concentric folds evoke the intimacies of the body, wreathed in a halo of fine fibres. All of Coopey’s works have a powerful haptic quality, not only in the compelling tactility of their textures and the lingering scents of the various vegetable materials. Together in the gallery they have an auditory effect of dampening, or quieting sound. A million miles from the crinkle of cellophane or the creak of plastic.

Dan Coopey 'Satellites' Installation View at Corvi-Mora, Courtesy the Artist, Corvi-Mora, London

This concise show is Coopey’s first at the gallery, and it is a hugely compelling exposition of the sophistication of the artist’s work. The sculptures here exert an irresistible physical attraction, while also evoking a complex of ideas that reach back to the earliest human histories as well as asserting, in foursquare fashion, the relevance of this craft form to the world we live in right now.

Caroline Douglas, Director

Satellites by Dan Coopey at Corvi-Mora

Corvi-Mora, 1A Kempsford Rd, London SE11 4NU