Featuring Yinka Shonibare, Ross Sinclair, and Berni Searle

Embedded within the land are stories which construct national identities. These identities are formed through shared history which gives us a sense of belonging.

Performing the roles of missing characters from national histories, artists in this section use photography to capture forgotten, overlooked or underprivileged narratives.

Using the language of self-portraiture, the artists use their bodies to reframe dominant depictions of race and class.

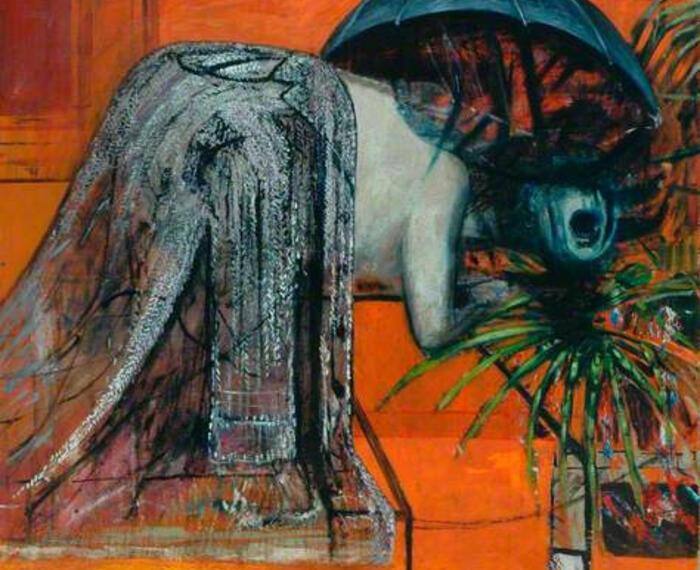

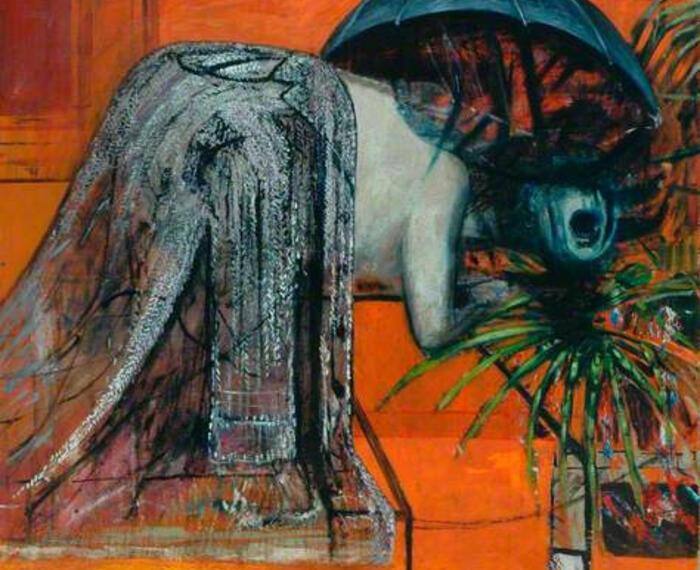

Staged like a theatrical tableau, Yinka Shonibare’s extravagant performance in the series Diary of a Victorian Dandy harks back to William Hogarth's A Rake's Progress as well as the enduring nostalgia for the Victorian period. In this series of photographs commissioned by the Institute of International Visual Arts (INIVA), Shonibare positions himself as the aristocratic cad at the centre of the unfolding drama.

The Victorian dandy is one of the most exuberant caricatures in British heritage, able to climb the social ladder to the height of aristocracy through quick wittedness and flamboyance. As the Dandy, Shonibare equates his self-described outsider identity, as a Black gay disabled artist, with that of figures like Oscar Wilde, both accepted and rejected by high society.

Photographed amongst the rich interiors of a Hertfordshire stately home, he challenges preconceived notions of British identity. Shonibare sees the Victorian elites as a “manifestation of sheer desire”. His character’s seedy corrupting influence revealing their underlying impulse to break free of stifling morality.

Shonibare’s performance reveals how figures of the Victorian era remain perennially fascinating, taking on contemporary cultural and political relevance with the passage of time. Initially displayed as a poster on the London underground in the late 1990s, many of the public thought the photographic series was advertising a new television period drama. By “shifting the central character”, the artist visually undermined a collective national nostalgia for the era.

In Ross Sinclair’s photograph Duff House #2, the artist stands with a shaved head, wearing only tartan shorts, his bare back displaying a large tattoo reading ‘REAL LIFE’. Sinclair began his REAL LIFE project in the early 1990s, experimenting across media to interrogate the nature of identity and, more broadly, the political and sociological dimensions of perceived reality. Here, in the aristocratic interior of Duff House, the figure he presents is dramatically at odds with the type of person one might expect to find in this setting.

The artist’s presence in the lavishly decorated space draws attention to the privilege architecture embodies, especially when constructing a national identity. The Baroque house, built in the 1730s for William Duff of Braco, is now part of the National Galleries Scotland. The stately home, as a site of manifest distinction between ruling elites and the rest of society has become the stage for bodily protest, begging the question ‘who’s reality persists?’.

The framing of the photograph truncates Sinclair’s figure but reveals a secondary portrait in a gilded mirrored reflection. The twin figures draw attention to the false binary of class, as well as our notions of appropriate behaviour.

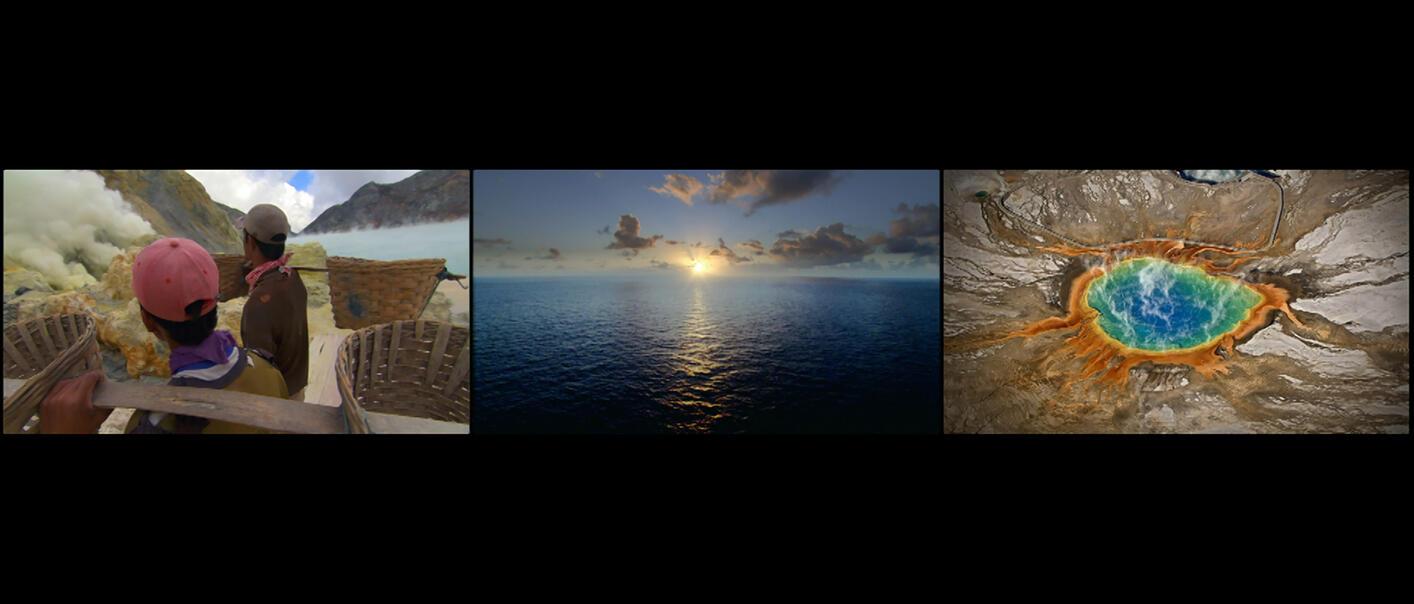

Berni Searle embodies a complex character in South African history in her self-portrait In Wake Of. Performing the deceased body of one of the miners massacred in Marikana in 2012, the artist covers herself with coal dust in a symbolic display of persecution.

In 2012, thirty-four platinum miners were murdered by the South African Police Service in violent attacks in Marikana to quash a strike over wages. Mining within South Africa has shaped not only the land but the political and social landscape. These attacks on Black working people compound memories of trauma suffered throughout oppressive years of colonialism and Apartheid. The massacre was the most lethal violence on civilians by the South African Police since the Soweto uprising in 1976 and the Sharpeville massacre in 1960.

Affected by the commodification of the miner’s bodies, Searle’s body acts as a placeholder for the people working in exploitative conditions. Drawing from her sculptural practice, Searle textures her portrait by caking her body in dust and dirt and holds shining gold Krugerrand coins in her limp hands.

As a woman artist from a mixed South African ethnic background, Searle’s self-portrait communicates the suffering of the widows who were left bereft and vulnerable after the miner’s deaths. Providing a sharp counterpoint to the many 19th century paintings of (white) female nudes by male artists in Manchester Art Gallery’s collection, the work asserts itself powerfully as politically charged self-representation. Searle presents her body on her own terms, uniting gendered, racial, and labour contexts into a single frame.