Featuring Zarina Bhimji, Amie Siegel, Seamus Harahan, John Akomfrah

We inherit the land from our ancestors, though this inheritance is often compromised by conflict, construction of borders, ownership, and power imbalances.

Each artwork in this section traces an inheritance between a particular history and an echoing contemporary context. Using the medium of photography and film the artists here engage with looking and being seen as political acts.

Zarina Bhimji’s photograph positions the viewer as if kneeling before a decaying upholstered chair. Our eyes fix on the seat of the chair, where the absent owner’s lap would normally be. We fix on a motif of flowers, inspect the chair’s gilded arms, and study the puckered rotting silk.

Taken in the eighteenth-century Harewood House in Leeds, the photograph makes reference to the history that lies beneath the richly furnished interiors and sweeping Capability Brown landscapes of the estate. Bhimji captures a colonial haunting.

At the time of Emancipation, the Lascelles family, then owners of Harewood House, received compensation for the ‘loss’ of 1,277 enslaved people in the Caribbean on sugar plantations they continued to own until 1975. Bhimji’s portrait of this dilapidated chair offers a commentary on the realities of the wealth creation that underpin inherited assets which are so central to romantic notions of Britain’s history. Through her lens, the artist places the viewer in a subjugated pose, looking up in an unequal exchange; humanising the viewpoint of the people whose labour made the Harewood fortune.

Bhimji focuses on one object to symbolise the inescapable imperial past. Part of a series which traces Islamic aesthetic influences from Alhambra, Spain, to English country estate landscape gardens, the photograph meditates on the legacy of aesthetic displacement. Her work fixates on a single chair to represent a history of ownership and exploitation.

Concerned with the “construction of value and movement of objects” Amie Siegel’s film Bloodlines traces various George Stubbs (1724-1806) paintings on their journey from private collections to a public exhibition and back again.

These artworks depicting family portraits, thoroughbred horses, inherited estates, and beloved objects are often still owned by the descendants of the people who commissioned them in the 1700s. The artist finds “stillness and sameness” amongst the families that populate and own Stubbs’ paintings. Siegel’s considered camerawork maps the lineage between the historic imagery and contemporary life.

By documenting the loans, the artist reveals systems of ownership and display which repeat themselves across histories and contexts. Seigel’s film tracks the artworks traveling across metaphorical spaces of private and national inheritance, blurring the lines of access in the process. Displayed and then removed from public view the film draws attention to a world of history sequestered in family collections.

Seamus Harahan’s film Holylands presents a very personal impression of a small area in Belfast. Filmed from his own window, Harahan views the area known as the Holylands, so named because the neighbourhood streets are called Jerusalem, Palestine, Damascus, Carmel, and Cairo.

In this area of Belfast, two communities live together: the students from Queen’s University and the locals. Harahan's works connect minute incidental actions to large-scale contexts. Over a year and a half, Harahan recorded fragments of background sound and documentary-style video looking out of his window. He cuts together cycles of movement and activity to create a documentary which uses people’s rhythmic movement to echo the ebb and flow of the area's economic and political stability.

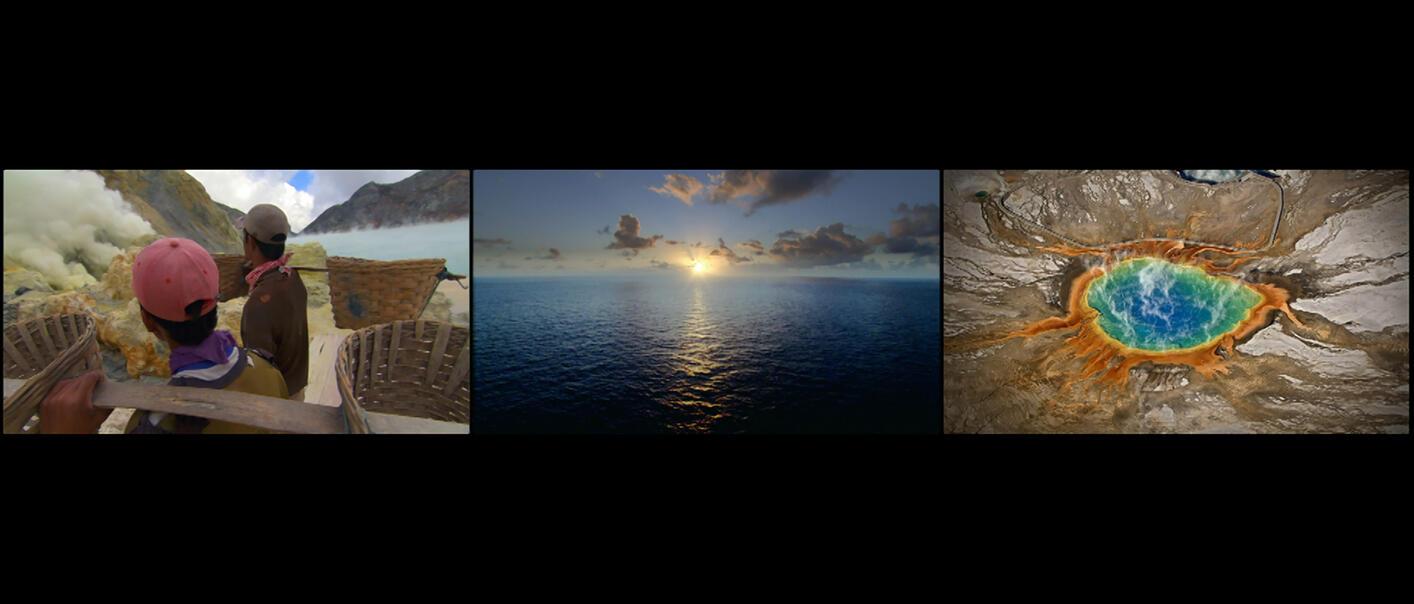

In John Akomfrah’s monumental three-screen video installation Vertigo Sea, he juxtaposes cruel and awe-inspiring images to tell the stories of people migrating across borders. Akomfrah layers strands of stories from different identities and narratives and plays them in dialogue with one another. The artist uses photographs, film, and archival imagery to conjure both the freedom of possibility and the overwhelming natural terror of the sea.

Akomfrah’s film brings together recurring motifs across historical sea voyages. He likens these sea crossings to Homeric journeys across uncertain waters to end suffering and arrive in lands of projected utopian possibility.

Huge migrations of people to Europe in the past ten years have prompted rhetoric that dehumanises migrants. Akomfrah seeks to reflect on language which placesblame and responsibility on individuals and unstable politics. He marks that often-drawn parallels between people smugglers and the Transatlantic slave traders strip this historical narrative of its specificity to transform it into a politically viable metaphor.

Akomfrah seeks an aesthetic and ethical language to mourn the people lost to the sea. Consciously resisting the direct depiction of human suffering, the artist uses imagery to exhume a lost history. Many have lost their lives crossing the waters; without a marker their stories are erased from history. Akomfrah’s work combats this erasure by landing their memories ashore.